An Overview of Scotch Regions

If you’re breaking into the world of scotch, the first thing to know is the different regions. They roughly divide the diverse options into five easy-to-discuss categories.

Consider the population of drinkers at a bar. Eliminate those who go for cocktails. Lose the craft beer fans and wine drinkers. Further remove those who only choke down shots to get drunk faster. The bar is now empty save for a few liquor devotees.

This group will generally enjoy a whisky, but scotch might elicit a few polite refusals. And most divisive of all are the scotches from the island of Islay, whose scent wrinkles noses several tables away.

But before I give the impression that Islay lovers are some elite breed of super soldier, let’s agree on one thing—these drinks are an affront to humanity.

To sip an Islay is to flip off every ancestor who ate a bad bug and died. We ignore millennia of evolution which built up a biological reaction toward what is—and isn’t—fit for human consumption. We smell the smoky aroma borne from burnt peat (literal death and decay set aflame!) and our lizard brains shout—this is poison! Nothing about this is not poison!

My own first drink of Islay, a Laphroaig, was a complex experience. The smell hits you first—woof!—and the taste delivers what was promised.

But after your eyes stop watering and the top layer of your tongue is burnt to ash, you begin to detect something within the cloud of smoke. You perceive the brine of the sea, the wood of the barrel, the moss and iodine and grain.

Islay scotches transport you to another place. For a whisky beginner who eagerly struggles to detect the most basic flavor notes—vanilla! cloves!—this is a transcendent experience. You realize that the flavor notes are a means to an end. The real reason you reach for an import is to experience a flavor which is distinctly exotic. You can almost hear water lapping against rock.

It also provides a lens to explore whisky in general. And while in my opinion nothing else compares to the striking terroir of Islay scotches, you can pick up some Highland scotches and taste the heather notes, or pick up a Speyside and get a sweet vanilla flavor.

Before going too far in this direction, there is a limit to how much you can attribute flavor to the region itself. It’s not as if the liquid in the bottle is a geographic inevitability. As a part of clever branding, Speyside distilleries learn what drinkers expect and generally deliver those experiences. Surely a Speyside distillery has access to the same peat which Islay distilleries use to give their scotches that rich, smokey character. But such a scotch would not taste “like a Speyside”. If subverting expectations were profitable, documentaries would be summer blockbusters.

That said, the expectations built up about a particular region are grounded in some sort of truth. When a characteristic flavor is not due to some regionally-exclusive ingredient, it is due to culture. Either way, the regions of Scotch remain an interesting and useful way to guide your exploration into your next favorite drink.

The Highlands

The Highlands are enormous, comprising the whole northern part of Scotland’s mainland. To a non-scot, the Highlands are what comes most easily to mind when one thinks of Scotland—punishing weather and rugged terrain.

Because of its size, the Highlands is the least cooperative region in committing to a certain style of scotch. Oban in the southwest has a fair amount of coastal smokiness, Damore in the north has a spicy but smooth character, while many of the most popular scotches—Macallan, Dalwhinnie, Glenmorangie—are sweet and floral.

The point is you will find a lot of variety here and it’s hard to pin Highlands down. The Scotch Whisky Experience museum in Edinburgh chose to call heather the characteristic flavor, but you could also make the case for oak or pepper.

My Highland Choice: GlenDronach Allardice

Speyside

Speyside distilleries are on the side of the river Spey. It’s a relatively small region compared to the surrounding Highlands, but over half of Scotland’s distilleries are here.

Also here are the two most popular single malt brands: Glenlivet and Glenfiddich. The expressions of both that you’ll find in bars are mild and unchallenging, but pleasant to drink.

The most characteristic flavor of Speysides has nothing to do with natural resources, but instead involves the casks the whisky is finished in. The distillation process of whisky is pretty quick, and what comes out the other side is fairly boring. The real richness comes from the years and years they spend aging in a barrel.

Speysides tend to use casks which had previously held sherry, and after ten or more years those barrels give the scotch a rich and fragrant finish. When I think of Speysides I tend to think of a luxurious and rich flavor from distilleries like Aberlour and Macallan. But with over half of the total scotch distilleries, there is certainly a lot of depth and counter-examples to explore.

My Speyside Choice: Balvenie DoubleWood

Lowlands

The Lowlands make up the portion of Scotland nearest to England. One argument for why England doesn’t have many whisky distilleries is that even in Scotland, the number of distilleries that far south is low. In fact the Lowlands had far more distilleries in the past but most folded during the tough economic times of the early 1900s.

Because there are so few distilleries it’s easier to generalize Lowland flavor. Think triple distillation, like what is common in Ireland. This gives it a very smooth finish and an almost citrus notes. Also, you will rarely taste peat or the more “rugged island” notes along the coast to the north. This tends to give Lowlands a mellow and gentle flavor.

As of this writing, only three distilleries export to the United States but the rising tide of the 21th century whisky industry raises all boats, including the Lowlands, and it’s thought that we’ll see more variety from this region soon.

My Lowlands Choice: Auchentoshan Three Wood

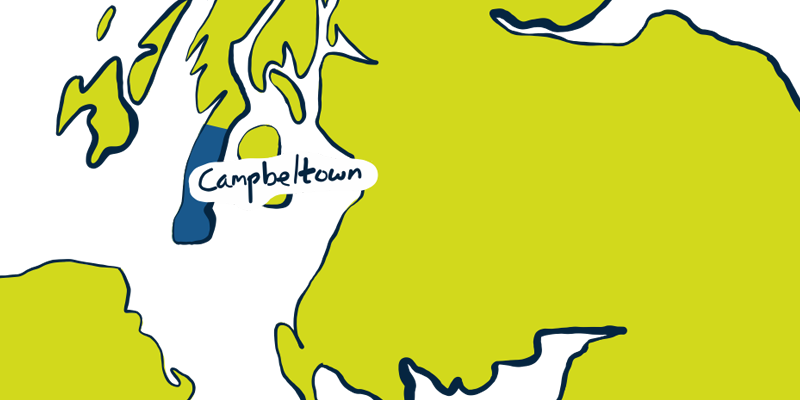

Campbeltown

Another region with a stronger past than present, Campbeltown refers to a small peninsula which juts out towards Ireland. Campbeltown’s flavor is even harder to pin down. The popular Springbank distillery produces three different varieties of scotch so different from each other that they go under different brand names.

Incorporating the other two major producers of today, Glengyle and Glen Scotia, doesn’t make generalization any easier. It’s thus more for historical reasons that Campbeltown is thought of as a distinct region of Scotland. While a powerhouse in the 1800s, today it’s rather quiet. But the devotion to quality scotch has not faded through the years.

My Campbeltown Choice: Glen Scotia Victoriana

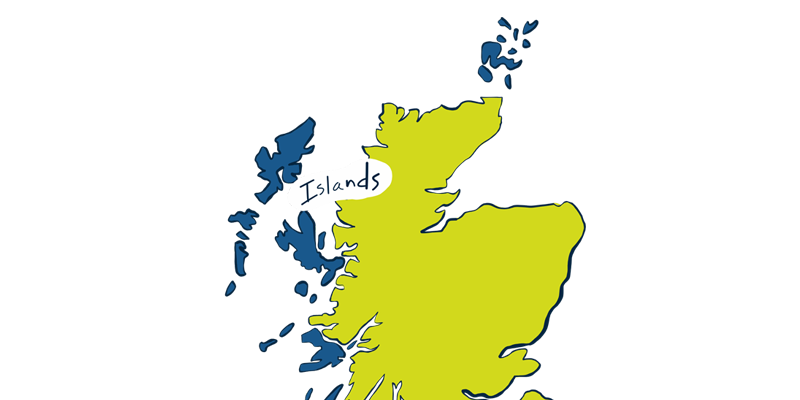

Islands

Scotland has 790 islands and, with the exception of Islay, 789 of them are grouped into this category. But though there is a lot of diversity, being islands means that you can generally expect the sort of flavors characteristic to coastlines.

Those islands with distilleries on them are along the north and west perimeter of the mainland. Here also there is a ton of variation, but you will generally taste peat smoke as an underlying flavor. This, too, has exceptions, as Highland Park’s main expressions have more in common with Highland whiskies despite being on Orkney island.

My Islands Choice: Highland Park 12

Islay

And then we get to Islay, which is the easiest to summarize and the hardest taste to acquire.

Islay, pronounced [eye-luh], is just one small island but it is home to nearly 10 distilleries. The three most popular, Lagavulin, Laphroaig, and Ardbeg, are within a 30 minute walk of each other. The industry there is built around whisky and whisky tourism.

Despite the tourists, it is a rugged and unforgiving island. And the taste does not go easy on you. The germination of grain which is used to make alcohol is stopped by heating it with smoke from burning peat. Peat looks like dirt, but it’s formed of an extraordinarily complex collection of decaying organisms. The smell of burning peat is like nothing else, and that smell survives years in the barrel and loses little of its potency by the time it’s poured into a glass.

I love Islays, but I’m currently having a bit of a reaction against them. It’s fun to perceive such obvious tasting notes, but now my interest is coming back to gentler whiskies with subtle flavor notes. I still come back to them near the end of the night, and I’ll never forget the taste of my first Laphroaig.

My Islay Choice: Ardbeg Uigeadail

~

Where to go from here? Go wide! If you realize that all the scotches you’ve ever tried are Speysides, know that you haven’t experienced the full variety of flavors out there. That’s a very good thing. It means that even if scotch hasn’t clicked with you yet, your dream dram might still be out there waiting to be found.